Corporate Landowners and their Powerful Creditors

Who owns the land is increasingly more about what owns it and credits it. Along with my co-authors John Canfield, Madeleine Fairbairn, and Kathy De Master, we follow the money. In an article recently published in the Journal of Peasant Studies, we trace corporations listed in tax parcel data back to their corporate family tree. We analyze parent and grandparent owners (when relevant) and also their creditors. We find that less than 30% of land owned by legal entities in our rural Illinois case study area traces back to local owners; further, we find that most business firms trace back to individual people or corporate owners with different addresses from those listed in tax parcel data. Taken together, this makes it hard to figure out who is responsible or is making the money, which is particularly problematic for rural communities.

Corporate Transfer of Capital

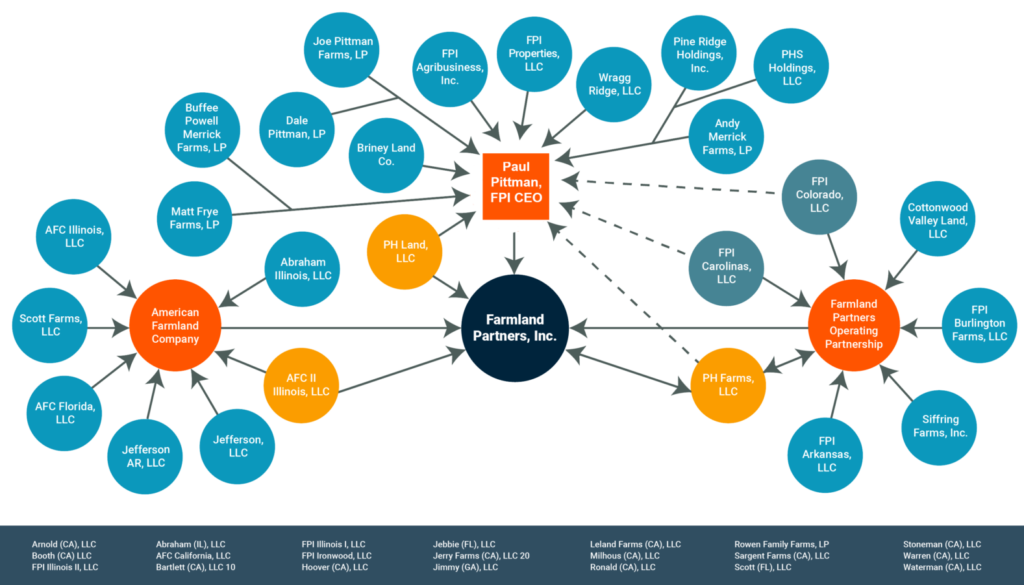

We detail how corporate structure gives business firms a leg up through complex webs of subsidiaries that limit their culpability in the event of wrongdoing. The most complex of corporate land holders like Farmland Partners (the self proclaimed largest publicly traded firm that barters in land) use their own subsidiaries to make loans to other subsidiaries. This allows them to make investments that an outside lender (like a traditional bank) might find too risky and hesitate to fund. Further, these exchanges of capital within the corporate web require little financial disclosure. The figure below details how Farmland Partners employs both internal capital markets (Farmland Partners Operating Partnership and PH Farms) and external capital markets (like Rabo and New York Life) to fund its land purchases. The acreage figures are specific to the case-study area of McDonough and Fulton counties in Illinois.

Rural Impact

Taken together, the law gives business firms advantages that smaller landowners and farmers do not have. In effect, local ownership moves away from rural communities, and with that the access and resources they so desperately need and deserve. Further, anti-corporate farming laws may be only a superficial solution to slowing down corporate ownership, because access to internal and external markets underlies financial investment in land.